(We are very fortunate to welcome back our friend Justin Collins (who spends most of his writing time over at Metal Bandcamp) with this guest review of the new album by Oskoreien, accompanied by a very interesting short interview of Oskoreien’s creator, as well as Justin’s equally interesting thoughts about the album’s subject matter.)

It was not even two months ago that we got to reacquaint ourselves with Oskoreien — the excellent but long-quiet black metal project of Jay Valena. Oskoreien contributed two songs to a split with Botanist. (Read my babble about it here.) I, for one, was very pleased to hear Oskoreien again, and was pleasantly surprised to listen to Valena try his hand at a decidedly more electronic sound than what he’d given us on his black-metal-meets-acoustic full-length. So you can imagine my delight when I learned that Oskoreien would be putting out a second album, All Too Human, hot on the heels on that split.

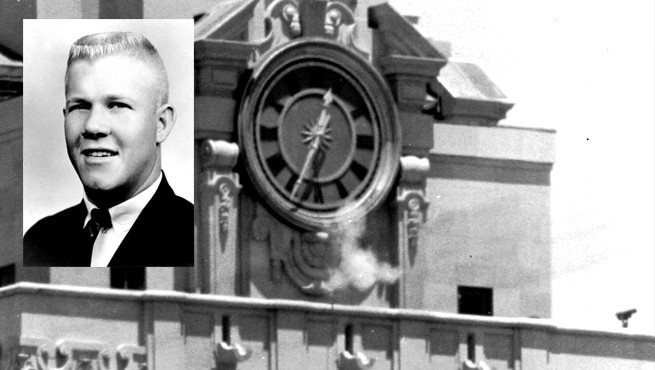

What kind of direction would Valena take this time? My first introduction to the album was a one-sentence description that Islander passed on to me from Valena, stating that, “It’s a concept album about free will inspired by the story of Charles Whitman.”

That’s an interesting choice, and if that name doesn’t immediately ring a bell, it might be because Charles Whitman died 50 years ago. Whitman is still relevant, though, because for lack of a better description, he was a very “successful” mass shooter.

It’s easy to think that American mass shootings is a modern phenomenon, given the seeming increase in the frequency and the heated debate about gun control that arises each time, but in 1966, Whitman, a skilled marksman trained in the Marines, killed his mother and wife before entering a clock tower on the campus of the University of Austin at Texas and opening fire on the people below. By the end of the day, he’d shot 49 people and caused 16 deaths before he was killed by police. You can read the short course over at the font of all human knowledge, but Whitman remains a bit of an oddity for a couple of reasons:

In spite of growing up with a very abusive father, Whitman was not the “weird loner” you so often hear about in these cases. By most measures, he was intelligent, reasonably well-liked, and successful throughout most of his life. But in the end, in his own suicide note, Whitman requested an autopsy be performed, and the examination revealed a brain tumor that may or may not have had a profound effect on his actions. In his suicide note, he said, “I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I cannot recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts.”

Valena was kind enough to answer some questions for me about all of this:

——–

You mentioned to Islander that the themes of the album are Charles Whitman and free will. Given the seemingly constant coverage of recent mass shootings, I can see why the general idea might be stuck in anyone’s mind. Why Charles Whitman in particular? I know his basic story–a very abusive father, training to be a very skilled marksman in the armed forces but ultimately washing out because of petty offenses, and the brain tumor found after his death in an autopsy which he himself requested — so I’m guessing one or all of those might be seen as things that stripped Whitman of his free will. Was that idea always with you, or did Whitman’s story end up making it part of the music?

I’ve always had an interest in the way the brain works, especially as it pertains to free will, and Charles Whitman’s story seemed like an appropriately extreme vehicle for exploring those concepts on a metal album. It’s impossible to point to any one thing tipping him over the edge into violent insanity – everything you mentioned certainly contributed – but the fact that he had a brain tumor impacting the center for emotional regulation in the brain definitely makes you wonder how much of a role it played. The fact that he was so self-aware of his changing emotions and growing lack of self-control made for some chilling suicide notes, and also led to the discovery of that tumor. His story essentially made possible a relatively clean-cut discussion of the interaction of brain chemistry and free will.

However, just to be clear, I don’t believe that anyone has free will – even those without glioblastomas impacting their amygdala. After all, where does a “normal” brain end and pathology begin? We know in modern times that nobody is actually born a blank slate; we’re imbued with predispositions from day one (and these begin to form in utero). We’ll probably never have an answer, and this could be debated forever, but given the complexity of our brains and the relative simplicity of our thought processes, it makes sense that there’s a lot more going on up there than we are consciously aware of.

I’ll never forget a discussion I had with one of my undergrad neuroscience professors when he explained his belief in the lack of free will – it might be a bit silly, but bear with me. Basically, our conscious self – what we refer to when we say “I” or “me” – is like a person stuck in a tiny room somewhere in our brains. When we “make a decision”, that “conscious self” is basically receiving a fax from the rest of the brain, where all of the thought processes have already occurred. Essentially our conscious selves are taking credit for, and rationalizing, decisions that have already been made. I know this answer is a bit rambling, but it’s an interesting topic. Anyone interested in reading more should check out the link below:

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/07/the-brain-on-trial/308520/

——-

Fine, fine, you say, but how does this translate into an album? Is this some plodding narration of Whitman’s crimes and/or an attempt to make excuses for the man? Not at all. Like consciousness itself, All Too Human resists easy analysis. Sure, there are lyrical hints that could describe Whitman, like the line, “No agency to escape that which is in motion,” in the opening track, or “My rage cannot be constrained within the walls of my flesh any longer,” in “Green & Maroon,” but these are part of more general meditations.

In fact, the name Charles Whitman never appears in the lyrics. If music exists to describe things that can’t easily be put into words, then a simple recitation of the facts over some chord changes doesn’t add much to the discussion. With this album, we’re left in the much more interesting area of symbolism and philosophy. For example, I asked Jay about the inspiration of including the Easter Island statues in “Maoi”:

——-

I really liked the symbolic connection of the Maoi statues. Are those a particular interest of yours? I don’t know much about the archaeological thoughts and theories behind them, but their immobile, imposing nature certainly lends itself to the theme.

My lyrical inspiration from the Moai was purely symbolic; I liked the imagery. Grand figures that have been eroded, but still stand. They don’t act, but are acted upon by the forces of nature. It’s not a perfect analogy for the lack of free will, but they represent how powerless our conscious selves are in the face of external influence.

——-

But I’ve ignored another big question for long enough: What about the music?

Put simply, All Too Human gives us unrelenting waves and layers of guitars, punctuated by and built around simple but achingly beautiful melodies. I’d still call it black metal — the requisite tremolos are largely absent, but Valena’s pained shrieks keep this firmly in black metal territory, not to mention the barn-burner “Ab Aeterno, Ad Infinitum,” which will give any blast beat addict more than their fill.

The music itself matches the imagery you might conjure. I can’t help but think of Whitman climbing those tower steps when I hear the ascending arpeggios in “Maoi.” There’s a bit of martial-sounding drumming in “Green & Maroon,” the very title of which puts me in mind of the USMC chant in the movie Full Metal Jacket: “What makes the grass grow? Blood, blood, blood.”

It’s an album that never lets go, and never lets you rest. The slow guitar strums in the middle of “Green & Maroon” lull you, but they persist as the music — and the menace — rebuilds. “Ab Aeterno, Ad Infinitum” toys with us a little, offering a heavily distorted guitar melody that slowly comes in and out of phase with its backing rhythm before the song explodes into full blast mode. We get snatches of hopeful melody near the end, before they’re obliterated with a mournful outro.

The closing song starts out with slow, stomping heaviness while Valena’s vocals slide even further up on the tortured scale. This is nicely contrasted with a slowing tempo throughout. The last full four minutes are a wind-down, in a way, but the tension never lets up, not even as the last, single note of the album fades out.

It’s entirely possible I’m only thinking about this because I recently reviewed it, but All Too Human reminds me a bit of Anagnorisis’s Perepeteia (see this link for a shameless plug…er, I mean my thoughts on that album). Both match a deep, often wrenching story with top-notch music. They’re two big highlights for me this year, and for all of the other crap that 2016 has dished out to us, musical or otherwise, I’d like to think 2016 is trying to make up for it a little bit with a work as stunning as All Too Human.

All Too Human will be released on December 2. Pre-order it here, and listen to one of the songs below:

http://oskoreien.com/album/all-too-human

http://www.facebook.com/oskoreienband

http://www.jayvalena.com/