(In this review Andy Synn turns his attention to the new album by Illinois-based Pan-Amerikan Native Front, which was released earlier this month.)

The more I think about Black Metal (and, trust me, I spend a lot of time thinking about Black Metal) the more it occurs to me just what an astounding paradox the genre is.

Founded by a bunch of no-good Norwegian punks (though if you called them “punks” to their faces you probably wouldn’t have enjoyed the response) whose back-story has since been retold and mythologised almost beyond recognition, Black Metal was originally just one big “fuck you” to the rest of the world, a purposefully introverted and isolationist rejection of ideas such as popularity, normality, and musicianship.

And yet, somehow, despite this – or, perhaps, because of this – it’s gone on to become not only a global phenomenon, but one of the most artistically adventurous and progressive genres in all of Metal.

How did this happen? Well, for me, it’s the underlying primitivism of Black Metal which makes it such an unexpectedly universal musical language.

Whether they knew it or not, those crazy kids somehow managed to tap into something truly primal and innately human with those ramshackle early recordings, something which connected with people all around the world and which they could then use as the foundation of their own art, and as a way to tell their own stories.

Stories like Little Turtle’s War.

Now, I’m honestly a little surprised we haven’t seen/heard more Black Metal artists and albums dealing with indigenous Native American history (I’m not saying there aren’t any, to be clear, just that they seem to be few and far between, and we could fill pages upon pages with discussion as to why that might be).

After all, the genre has – perhaps ironically – proven itself to be nothing if not culturally adaptable, with bands from all different countries and backgrounds using it as a canvas on which to express themselves.

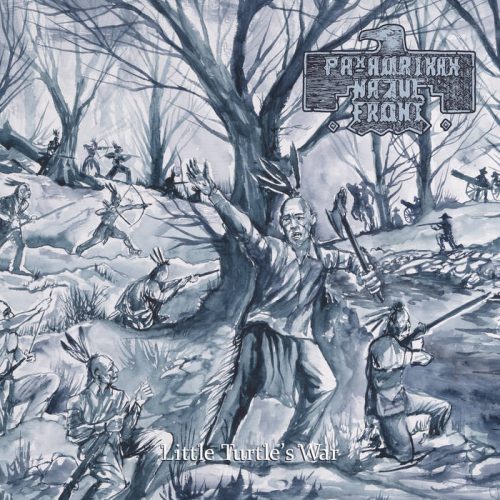

And Little Turtle’s War is a prime example of that, dealing as it does with a period of history (specifically the late 1700s) where a confederation of Native American tribes waged a war of resistance against the encroachment of US settlers onto their lands.

With casualties and losses on both sides, including several instances where the US forces suffered some of their most severe and stinging defeats, and an ongoing legacy which still resonates to this day, it’s obviously fertile soil for Black Metal whichever way you slice it, and although the events depicted here may be several hundred years in the past it’s clear from the word go that the emotional connection on display throughout this album is both very real and extremely raw.

Which brings me nicely onto my next point – Little Turtle’s War is far more than just a history lesson. It’s a damn good album in its own right, one whose visceral energy and palpable fury are easily the equal of many bigger and more famous bands.

Musically speaking Pan-Amerikan Native Front is still heavily indebted to the icons of Black Metal’s “second wave” – Mayhem in particular seem to be a central touchstone for the band’s ragged-edged yet furiously focussed approach – but also, on certain songs (most notably the hammering “Power of the Calumet Dance”) hint at an even more ferocious, War Metal inspired sound.

But all this fire and fury is tempered, and dare I say strengthened (which, to be fair, is what the word “tempered” should imply), by the band’s more melodic inclinations, which elevate tracks like the heroic “The Battle of the Wabash” and the prowling strains of “The Great White Beaver Lurks” to new heights without losing that innate connection to the music’s more primal roots.

This marriage of raging intensity and riveting melody reaches its apotheosis on the album’s final track, “nakaaniaki meehkweelimakinciki”, whose reckless metallic rampage eventually gives way to an utterly sublime, soulfully sombre mid-section of both epic, and elegiac, proportions, before one last burst of bombastic blackened barbarism brings things home.

Of course, absolutely no-one, not even Pan-Amerikan Native Front’s own Kurator of War (who handles everything on this release himself) is going to pretend that Little Turtle’s War is some sort of paradigm-shifting redefinition of the Black Metal ideal. It isn’t, and it’s not meant to be.

But what it is, ultimately, is further proof that the marriage between the traditions of Black Metal and the traditions of other cultures, other voices, other histories, only serves to make the genre stronger.

BANDCAMP:

https://pan-amerikannativefront.bandcamp.com/album/little-turtles-war

FACEBOOK:

https://www.facebook.com/Pan-Amerikan-Native-Front-327034784324273/

Nice write-up for a good release (snagged myself a tape)!

Do check Lionoka – Tides of triumph over at Old Mill Artifacts

for a different spin on similar approaches!

Ok, I’ll be the guy everybody accuses of being an SJW: is the person behind this project actually Native American? Maybe I’ve just been burned by too many fash wannabes, but the FB description, “Black metal project–an indigenous-centered narrative on military conflict against Western aggression,” says “indigenous-centered narrative,” not “indigenous narratives told by indigenous people (or person).” Satan knows that people with no tribal connections have been cosplaying as Native Americans for a long time, and it’s usually pretty gross.

Metal-Archives identifies Kurator of War as Alan Avitia, originally from Mexico City. He says in the recent Decibel interview linked below that he has native ancestry (and remember that the band’s name is connected to indigenous peoples throughout “the America’s”, not only North America).

https://www.decibelmagazine.com/2021/02/05/album-premiere-pan-amerikan-native-front-little-turtles-war/

Ha, I mean, I mean I can call you a “SJW” if it will make you feel better but… I do understand your reticence.

After all, I think we’re all aware of the prevalence of people claiming “native ancestry” because their great-grandma’s great-grandma claimed that HER great-grandma was actually a native american princess… but, in this case, from what I can tell, the cultural connection is very real and Kurator has really done his homework exploring his roots and the history therein.

This isn’t another Ghost Bath situation (and the music’s 10 x better anyway).

Same goes for Infernach & Ixachitlan, as in, theyre non-wannabees?

As a non-American, this discussion, although I understand its importance, is a bit alien to me. Apart from some cases I read about in the news, how common is claiming such ancestry and to what purpose, exactly? I can think of some reasons, but wouldnt want to speculate baselessly…

There’s plenty of reasons to claim native ancestry. One is that tribal membership confers certain rights, particularly hunting and fishing rights and rights on reservation land that are not available to non tribal members. Another is that it is a way for white people to claim to be minorities in order to take the moral high ground. Because native blood is often found in such small fractions, it’s not necessary to appear native in order to claim ancestry, so there’s little way of knowing when someone lies.

Good point. I think I’ve moved on to preferring “cuck” or “simp” at this point. SJW is so 2018.

Nah, tik-tok has taught me it’s all about “fwunge” these days.

Why must the narratives be told by native people? Can’t other people with a genuine interest in, and proper research of, that culture tell the same story?

If you were to indiscriminatively enforce a rule of dismissing any band that tells a story of a culture other than their own, you’d have to dismiss a large number of bands across many different genres, including the countless bands outside of Scandinavia and Iceland that use “norse” or “viking” themes in their music. Sure, some bands that use themes from cultures other than their own are cheesy, ridiculous or even flat-out bad, but what about the good bands? Should they, too, be dismissed because of some principle?

I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt and assume you’re actually asking this question in good faith (as very often it’s disingenuous – you’ll note that even here you’re basing it around a hypothetical “What if…” that I didn’t actually say) and respond thusly…

First off, I’m sure even you will admit there’s a difference between just “telling stories” and having a legitimate connection to the material, especially when it deals with the events of history that have directly affected your people and your culture through the years. And while there’s not necessarily anything wrong with the former you often get a better and deeper level of insight in the latter case.

And, secondly, I’m sure you’re aware of the importance of CONTEXT, and rather than just making a sweeping generalisation it is perhaps important to look at the actual history of native american stories and identities being coopted for profit down through the years, which makes it particularly interesting to highlight instances like this one where that’s not the case.

First of all, my comment was a reply to JC, so I’ll choose to disregard that utterly uncalled-for insinuation in your first paragraph.

Now, onto the actual discussion:

You say that you often get a deeper level of insight into a story if the narrator has some connection to the story. While I don’t necessarily disagree with that sentiment, the very premise in my question was that the outsider has done sufficient research on the matter. In that case, I don’t see how the narrator’s cultural affiliation would make much of a difference to the story.

While context is important, if it’s a question of principle, you do have to generalize. If you start discriminating on a case-by-case basis, you would, obviously, no longer be applying a principle. And I honestly don’t see why holding different peoples/cultures to the same standards would be a radical idea. Discriminating between peoples/cultures, on the other hand, sounds, to me, like a genuinely terrible concept.

(Also, I’d very much like to know what “even you” is supposed to mean in your second paragraph.)

I’m a historian, and while my speciality is the World War 2 Eastern Front, I have also extensively studied Native American military history. This means I’m quite familiar with the literature covering the wars for the Old Northwest of the United States. For anyone who wants to learn more of the background to Little Turtle’s War and Tecumseh’s War (Tecumseh fought in Little Turtle’s War as a protégé of the Shawnee war leader Blue Jacket), the best one-volume starting place is Bil Gilbert’s God Gave Us This Country.

John Winkler covers the specific battles in more detail in six well-illustrated volumes of Osprey’s Campaign series. These are, chronologically, Point Pleasant 1774, Pekuwe 1780, Wabash 1791, Fallen Timbers 1794, Tippecanoe 1811, and The Thames 1813.

A fun look at this era, told through short biographies of colorful personalities, is comic book writer/artist Timothy Truman’s Straight Up to See the Sky.

Finally, Allan W. Eckert’s The Frontiersmen was long tbe gold standard for the subject. It is still easy to find in many libraries or as used copies. However, it is now understood to be heavily fictionalized and to have many errors in detail. It still makes entertaining reading, and will give a feel for the struggles of that time.

Thank you so much for this unexpected treasure of a comment.

Thabk you for your post. Im a historian too, specialized in colonial violence and revolutionary movements. I shld delve into the subject matter above…very similar, yet so different.