(The subject of this very extensive and engaging new interview by Comrade Aleks is Adam S., the lyricist and chief songwriter of the distinctive Slovak metal band Malokarpatan, though he also discusses another personal project with an album in the works.)

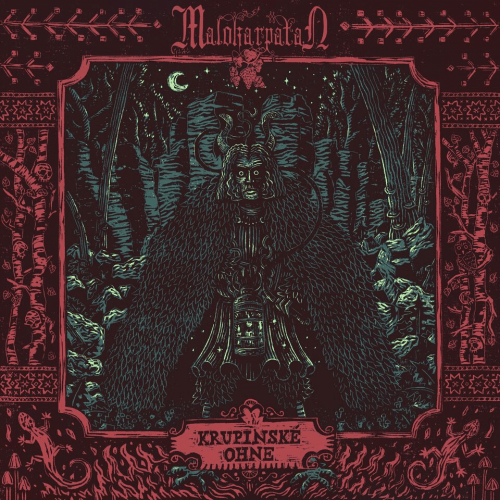

If you haven’t heard any of Malokarpatan’s albums, I bet you know about them anyway – no one could skip over the eye-catching artworks of Stridžie dni (2015), Nordkarpatenland (2017), and Krupinské ohne (2020). Slovakian pagan traditions shine through these authentic covers, and as you might surmise, the guys write their lyrics in their mother tongue. You’ll find translations easily enough, for example at Metal-Archives, and should find them if you’re searching for new poetic discoveries.

But probably we should start with the curious fact that Malokarpatan perform an authentic (again authentic!) mix of reckless yet tricky, non-trivial, heavy and black metal. Heathen energy, the pounding pulse of the wild, and a haunted atmosphere complete a sonic canvases filled with details and nuances…

I’ve found Malokarpatan in my “need-to-interview” list, and though their last record Krupinské ohne saw the light of day nearly one year ago, I believe you don’t need to wait for another official release to talk with a band you like and respect. I’m grateful to Malokarpatan ideologist and chief song-writer Adam S. for this deep and entertaining interview.

******

Hi Adam! How are you? What’s going on in the Malokarpatan camp?

Hello! Not much at all is currently happening in the Malokarpatan camp, I spent the majority of this year in Sweden where is now my second home, so I haven’t even met any of the members since last year. I have the next album written, but this time I am in no hurry to churn it out as fast as possible. We did three albums in a 5-year span which is satisfactory enough for me. I want the material to breathe a bit, so I can change some parts here and there if I feel like they didn’t age well.

Don’t you feel pressure, as if time is racing? Covid strikes here, climate changes hit there, and it seems like we have not much time for fun.

I only felt a pressure after the debut album. Just wanted to do things fast while I’m filled with ideas. Currently I have actually even more ideas than back then, 6 years ago. I’ve developed four different concepts for the next record, complete with lyrics and everything. And sometimes things move so unpredictably and fast. Since the last time we spoke I am in fact in Slovakia currently and started working more actively on the album. I felt this sudden inspiration which always starts an album for me and just went along automatically. I’ve found which of the different possible directions feels best for album number 4, and the other ideas I’ll keep for the future. Just expect something different again, as we always do. While not at all being a direct musical influence on Malokarpatan, I always was in awe how David Bowie managed to do each one of his albums differently, especially the ’70s era. This is something I enjoy doing myself.

Okay, back to our daily agenda. The band’s history is relatively short but for these seven years you’ve made more noise than the lion’s share of other underground bands, and the reason is Malokarpatan’s authentic concept. You performed different sorts of black metal since 2001 when Helcaraxe was formed and then it was reformed into Remmirath. How do you now see all these changes in your tastes which led you, as well as HV and Peter, to Malokarpatan?

Basically the only major change in my music tastes happened around the time I got into my early 20s – which were the Remmirath years. I got into metal very early on through my older brother and had been listening primarily to metal all the time up to my 20s, so at that time I felt a need to expand horizons. I was exploring a lot of different music from all parts of the world and those good records I discovered stayed with me to this day; the rest didn’t stand the test of time.

Mostly I am into different kinds of experimental, psychedelic, progressive etc music from the golden ’70s era – those influences made their way also into Malokarpatan (even the debut album has a bit of a subtle moog synthesizer). After Remmirath I went a lot into territories outside of metal or even rock, and the more conservative part of me felt a longing to do something very metal that simply just rocks, musically speaking. One thing I stopped doing for many years was second-wave inspired black metal. The Remmirath demo was in that vein, and although I never stopped listening to that kind of music, I simply felt it is oversaturated by way too many bands doing the same thing, not necessarily better than the pioneers. So I just wrote some songs to sort of put them in the archives and didn’t really record any of it. Last year the nostalgic part of me finally won over and I started recording this project that continues in that vein – it is still in the works now, but I hope to somehow get it out during this year. Meanwhile Malokarpatan has carved its own niche and I’ll just continue doing it whenever I feel the call to make a new album.

Stridžie Dni was a blast! Dozen of reissues serve as proper evidence of its popularity (for the underground scene). How long did you shape the very concept of Malokarpatan as we hear it on this album?

Thank you very much! It was a very spontaneous recording, which is where its magic lies I guess. I wanted to make some ’80s-influenced black metal with Temnohor, the former singer, as that’s the music we usually blasted when we went to our forest hike trips in the Carpathians. In his own one-man band, he used this local dialect of Western Slovakia and I found it a fascinating thing to expand upon, so even though I wrote all the music and lyrics, I had him in the back of my mind. I had the music first, so the concept came only after that, although quite naturally after I got this idea to mix those two worlds. Some people still have that album as their favorite and I can see why, though as the creator I always like the last recording the most.

Didn’t you fear you might disappear unnoticed and misunderstood with this mix of proto-blackened-heavy metal and local authentic aesthetic? The lyrics and Lívia Gréková’s creepy killer artwork only add to the charm of the album…

You could put it the other way around basically – I had no idea or plan for it to become popular, so it caught us all by surprise. I thought the concept was way too obscure for outsiders, and on the other hand, Slovak metal fans on average tend to be more into the modern forms of metal which we stay away from, so I didn’t expect any bigger success back home either. At least according to online statistics, the majority of our fans seem to be from the USA, which is a quite odd phenomenon. The other big base we have is in Poland, where it makes sense because our cultures are highly similar. I suppose abroad it’s the exotic factor – same way as for me, let’s say ’80s South American bands are fascinating because of how different their backgrounds are to mine.

It’s said that: “Stridžie dni (“The Witching Days”) is a celebration of the countryside in Western Slovakia, with all its grotesque myths and lore. All lyrics were written in local dialect and they mostly deal with folklore legends based on rural witchcraft, drunkenness and also national pride. Like the Slovak soul itself, these songs are often both grim and humorous, merry and melancholic at the same time”. Were you sure this attitude toward lyrics would work? You could just utilize stories about strigois, etc., and and none would blame you!

I’ll be short on this one, as I have already addressed it in detail in my interview with Niklas of Bardo Methodology. The lyrics have always been available to read in English translations both online and on the physical records, so any misunderstanding of what they are about is purely the laziness of everyone who didn’t bother to read the translations. The statement you mention was meant for the debut album only and the “national pride” part was only the last song on the album, which actually tells an old Slovakian folktale. As I said in the above-mentioned interview, it gets about as nationalistic as Tales From the Thousand Lakes by Amorphis. My roots are in the ’90s where these topics were common/normal and never politicized – at least I can’t remember anyone trying to see politics in the lyrics of Mother North, one of black metal’s most popular cliché songs that any beer-guzzling German at Wacken can sing from his sleep.

Anyway, most people were sentient enough to see these subtleties, so the problems were very few. It was worse with the drunkenness topic, as that is a complex one – it is actually part of the dark side of Slovak identity, this image of mountainside rednecks puking on the floor of the local inn. We showed that element too, as it belongs to who we are, and we never tried to paint a romanticized picture with braided hair women standing in sunlit fields. All black humor aside, it in fact has a tragic undertone.

Thanks for the detailed answer even though the question is so trivial for you. I think you’re right, it was far easier in the ’90s, and actually the part about “national pride” didn’t catch my attention at first. But now after your answer I’m wondering how is it ok or safe to be pagan, or to perform music with a “pagan” tag in your area? Here in Russia it’s still more or less a “safe” musical direction, but as far as I understand the situation it isn’t as cool as in the ’90s, and governments slowly start to get interested in everything that isn’t “normal” for their good old totalitarian ways.

It’s hard for me to answer from a personal experience sort of view, because we are not that kind of a band. The lyrics often come from, let’s call it the pre-Christian lore of our lands, but I never felt a desire to be part of any of these so-called pagan scenes. Most of it seems very kitsch and one-dimensional to me. Even from a spiritual point of view, I wouldn’t see myself as a pagan. I’m interested in the left hand path side of those things, and more broadly I guess you could say my beliefs are Gnostic.

When it comes to problems of neo-pagans with government and police, there were some in Slovakia but it was connected to politics, so it basically had nothing to do with music. In general, it’s not as big a phenomenon here as it is in Russia or Ukraine, so I would say the common person views these Rodnovery people just as eccentrics. I for one never understood their need to dress up in all sorts of costumes, as if the spiritual element wasn’t far more important than what you are wearing. The overall Slovak identity I would say is a fragile thing and definitely in crisis when confronted with the current world (as it was in the past also – our history is complicated and mostly grim), so we just do our small part in preserving some of the folklore in our music and lyrics.

I remember… actually no, I can’t remember… the name of that band which gained some financial and media support from their government for promoting local cultural traditions. Hamferð from Faroe Islands maybe? However… did Malokarpatan ever get any support from the government due to keeping Slovakian cultural traditions alive even in this twisted metal way?

I think also Solefald received some state support for their Icelandic Odyssey albums, if I recall correctly. But no, we never had any contact with the Slovak government, nor would we wish for it. Our last album was nominated for a radio prize in Slovakia, but we didn’t even inform about it because we have zero interest in such things. This kind of music should always stay in the shadows outside of mainstream society. Just watch the old videos of The Kovenant receiving Spellemannprisen to see how ridiculous this can all become.

You did took part in exclusive splits, Samhain Celebration MMXVII (2017) and Holbaard Dzírobrad / Kartanon herra (2018). Most of these bands play black metal, so do you see Malokarpatan as an integral part of the European black scene? Do such things mean anything for you nowadays?

The bigger split was just a sort of rarity release intended only for the German festival where we played with the other bands. So we were not in contact with any of those bands except Mosaic, who were the curators of the whole idea. The Demon’s Gate split was a more personal affair, as those guys are our personal friends whom we met many times through the years, although nowadays they shifted focus more on Chevalier, which is also a killer band. I personally feel that our music is a continuation of the early Czechoslovakian black metal tradition, or if speaking more broadly, one could also say Iron Curtain countries in general – there you could include Kat from Poland and Tormentor from Hungary. The idea that black metal is simply a way to play music came from people who misunderstood the second wave. Whatever is one’s personal view of Euronymous, you can just read his old interviews where he would be the first to say that Norway was just elaborating on traditions established already before the rise of their scene.

What are you meaning as you tell about “second wave inspired black metal”? You have mentioned it for the second time.

Everything that came after Norway became the trendsetter scene for the whole world. It’s a difficult topic – I absolutely love the early Norwegian bands and how each one of them competed to have their own, unique take on the genre. The negative side of this was that the whole world then tried to sound like them, and with that was lost this amazing diversity of early black metal from 1982-1992. Back then, each part of the world kind of had its own sound – Eastern Europe, South America, Southeast Asia, Australia, etc. No two bands really sounded alike, but then everyone tried to sound like Transilvanian Hunger and In The Nightside Eclipse by 1994 and later. I definitely have nothing against taking the Norwegian sound and developing it into your own personal thing – as that’s something I’ve been part of myself outside Malokarpatan. I just dislike the soulless copies that try to sound exactly as those albums do and add nothing of their own. Plus it’s always tragic when people think black metal came into existence in 1992 and everything before is regarded as thrash metal or something.

You used a lot of different samples and classical excerpts taken from Eugen Suchoň, Jean-Joseph Mouret, and Jules Cantin for your second album Nordkarpatenland. What was your vision behind this piece? How does it differ concept-wise from Stridžie Dni?

I was always a big fan of using samples in music – be it more in-your-face kind of stuff like Impetigo, or more sophisticated approaches where they merge with the music seamlessly. My intention with any of our albums always is to transport the listener into a different world, and these movie and classical samples are just a means to enhance that. I want the albums to feel almost like a theatrical play.

The difference of Nordkarpatenland compared to the debut was that it was more focused on catchy ’80s-style songwriting – while keeping all the band concepts intact, I just wanted the album to have the same effect as if you’d put on a classic album from Judas Priest or even Led Zeppelin. Memorable songs that each have their own specific mood. Lyrically, it was kind of a kaleiodoscope of different types of malevolent folklore spirits which our ancestors believed in.

Do you believe in these… natural or pagan powers… yourself? How do you see the spiritual aspects of Malokarpatan? Or is it all about music and that’s it?

Yes, I’ve always had spiritual beliefs since I was a child and a general interest in the unkown and supernatural. In Malokarpatan I keep it subtle, as there are so many bands already that are all about this, often to the point where they forget to make interesting enough music to accompany their painstakingly made lyrics. Krupinské ohne is the only album so far where I elaborated a bit on what my personal beliefs are in this; most of it you could find in the last two songs, including the accompanying text parts which are not part of the sung lyrics, just serving as extra details and explanations for the happenings.

Adam, you, Peter, and HV have added new instruments to Malokarpatan’s bizarre arsenal during your work on Nordkarpatenland. Was it difficult to incorporate and record all these additional instruments alongside your ragged tunes?

Not difficult in the technical point of view, but we didn’t have enough time left in the studio to record some more of them, which I had intended. So for example glockenspiel, which I brought to the Nordkarpatenland sessions, only showed up on the third album simply because we had time to record it by then. In the end I am satisfied, because it helped to differentiate Krupinske ohne even more from the older material. I like to move a bit into new territories with each album, while keeping alive what the band is all about.

I have a small collection of these less usual instruments and will definitely use more of them on the next record too. Same as the samples, they are there to help us take the listener into our strange little world. I really like how ’60s psychedelic groups used this commonly to enhance the oddness of their LPs. It can work perfectly well in metal too, as long as it doesn’t take over the soundscape. Lugubrum on their recent albums have a fantastic use of these things.

This album is also marked by your collaboration with Tomáš Kohout and Annick Giroux. How did you lure them into Nordkarpatenland?

Annick is a friend and we like each other’s music so that was an easy one. I think she can conjure excellent melancholic atmospheres in Cauchemar, so I asked her to do some of that for us and was very pleased with the results. She also joined us live on stage when we played in Canada back in 2018 – that was a great, memorable night.

Necrocock was a bit different situation, as he is basically a childhood idol sort of person for us. Most people of course know him from his past with Master’s Hammer, but what many foreigners are unaware of are his nowadays projects. I recommend checking his YouTube channel to enter his wildly original world of eerie atmospheres, sexual perversions and bizarre fascinations. It’s hard to explain to someone from a different cultural background, but his music strongly evokes this sort of “Czechoslovak Gothic”, this uncanny feeling you get from old local movies, books, paintings etc. If you ever watch the 1969 Czechoslovak movie The Cremator, you will feel that instantly. I wanted that element in the album, and to have an idol from our youth there was an amazing feeling.

Stridžie Dni and Nordkarpatenland did set a high brand for Malokarpatan, I believe you know that well. Did this fact haunt you when you were working on the third album Krupinské ohne? Were you searching for new forms of expression or new techniques in order to create something different this time?

It was mainly Nordkarpatenland that made us somewhat popular in the international underground. I intentionally made that album catchy and memorable, like classic metal records from the ’80s used to be. I guess that might have been a breath of fresh air among all those bands using disharmonic non-riffs which you forget the second after you heard them. The easiest way to continue would be to make a Nordkarpatenland Part 2, but that would be way too cheap. So we moved into a far less accessible direction, taking inspiration from ’70s prog rock or even odd albums like The Elder from Kiss.

It brought very mixed reactions, as I kind of expected, but one could observe that the album won more and more people over time, when they revisited it and paid enough attention to it. The first two albums are something you can blast at a party while drinking beer, the third one is purely for lone listening with headphones on, focused on the concept story and all. Reinventing our concept with each release is what keeps the band alive for me and if we ever get stuck in our own formula, that will be our creative death one day if it happens. So far I can just say that I again have a different approach ready for the next record.

The album is based on true stories of witch trials. How topical does this theme sound today? Is it about witchcraft? Is it about a misfeasance? Or is it about general intolerance?

In general, it is of course an extremely cliché topic in metal music. King Diamond did it 30 years ago already. So we definitely weren’t trying to break new ground with that. I think so-called clichés can be a great thing, as long as you do them justice. One can look for example at the Hammer Horror movies – all they did was revive the same old gothic monsters that Universal Studios were working with in the 1930s. But they did it in style and brought new elements. My approach to this topic was roughly in that vein.

It is a largely forgotten part of local history, so I decided to bring back the story of those people to life. But as you implied, it has more dimensions than the basic obvious one. One is religious – I genuinely believe in spiritual forces that are superior to mankind, and I see the secret cults of these countryside peasants as a clandestine continuation of pre-Christian agrarian worship, with even deeper, gnostic implications. Which brings us to the third element – the social. That one is the most subtle, as after all we are working within the black metal cosmos and things like these have little place in it. But one can just think more widely of the witch-hunt phenomenon, as something that never left us and still exists today. Heretical voices are as unwanted today as they were back in the 17th century, when these old peasant women were lit alive.

At least the last two Malokarpatan albums were recorded at Hostivař, Prague. Why did you choose this studio?

A mix of practical and nostalgic reasons. It is the nearest studio that works with music similar to ours, which makes the process easier and faster and you don’t have to explain to the engineer why you need a loud distortion, etc. Metal music is not exactly the biggest thing here, so the options are limited. The other reason is that Master’s Hammer recorded their legendary The Mass demo there back in 1989 and it’s still the same place ran by the same guy behind the desk. Prague in itself is famous for its gloomy gothic architecture and an overall mystical feeling streaming from its history – the alchemists and occultists who were hosted by Emperor Rudolf II, the old Jewish cemetery and the Golem legend, the House of Faust, etc.

As Malokarpatan is on hold for awhile, you say that something new from Krolok may come soon. Did you finally join this band too?

The second Krolok album is already recorded and is set to be released early next year on Osmose Productions. I never was a member of the band, but I did collaborate with it in different ways over the years. This time I was asked to write all the lyrics for the album, for which I had a time frame of just two days. I embraced the challenge full of inspiration and I am pleased with the results. Some of the lyrics have basic ideas or a few lines from HV/Graf von Krolok, the rest is my work. It will be a curious album as it has more ’80s-inspired riffs than the debut, but at the same time also goes more atmospheric through an increased use of synthesizers. The end result sounds rather interesting, yet very different from Malokarpatan.

Sounds exciting! Do you see yourself as a real metal fanatic who’s ready for everything, to take part in another band or project? Or do you see your approach as a sober one and you know when to stop if your passion demands too much time or energy?

Actually this is really difficult to me, to work with other people’s music. Even when I try, I just am not able to put my heart and soul into it 100% like when I work with my own ideas. So I prefer these more distant collaborations, and writing lyrics is something I tend to enjoy doing for others. I just tried earlier this year to join one band here in Sweden where I now mostly reside, and even though I really like their music, I just couldn’t break into it, the rhythms they incorporate were already different to what I am used to, and so on. I guess it’s like way back in elementary school days – I never liked working on group projects and would rather do my own thing.

Adam you also have told about your black metal project with “a long delayed album”. What can you tell us about it? What stopped you from recording this material earlier? What do you aim to express through it which you can’t channel through other bands?

This project is something I have dragged along with me for years and never really realized or finished it. The earliest demo recordings reach back to 2010, but it actually contains some of my earliest riffs ever written, from around 2000 – 2001. In 2020 I finally decided to record a full-length, which is now in the final stages after many delays. The reasons for all this were several.

Style-wise, it is closest to the Remmirath demo from back in 2005 – that’s the kind of music I originally came from. This sort of mid-’90s style with a “foresty” feeling coming from folklore, which though has nothing to do with the folk metal abominations popular today. The prime example of this style is Satyricon’s Shadowthrone album, but also stuff like early Dimmu Borgir, Ulver, the first Borknagar, Grimm-era Ancient, Thy Serpent, the sadly overlooked Norwegian Naglfar and their brilliant demos, Forgotten Woods on Sjel av natten, etc, etc.

I avoided recording anything in this style for years, because I thought in general the second wave style was oversaturated by way too many lousy bands in the 2000s and I didn’t want to add to the crime. With all the time passing, I felt more and more this longing to return to it, and as it came to a point when almost nobody plays music with that kind of atmosphere anymore, I decided the time was right. Funnily enough, I see now a few bands are emerging trying to recreate exactly that mid-’90s feeling. I should’ve done it back then in 2010, haha.

First it was called Sylvan Abyss, but as I progressively moved more and more towards themes rooted in Slovak pre-Christian lore, I changed the name to Stangarigel – a strange rock formation in Slovakia which is mentioned also on Krupinské ohne. The line-up will be just me and my older brother doing drums and vocals. We grew up together with the same music, so in the end it was the most natural decision.

And I bet we’ll take a closer look at Stangarigel when the album is finished and ready to release. Thanks for your time Adam, it’s much appreciated, I hope we’ll have a chance to talk again soon.

Hopefully this year! It’s sort of a cursed project haunted by neverending delays, but I won’t give up. Thank you as well and hear you some other time!

https://malokarpatan.bandcamp.com/

https://www.facebook.com/malokarpatan?fref=ts