photo by Betsy Whiteman

(In this interview with writer Jordan Whiteman, Comrade Aleks delved deeply into the story behind Whiteman‘s recently published book about the history of dungeon synth, and the passion required to make the book a reality. Like the book, the discussion is essential reading for any fan of the subgenre, and for anyone interested in exploring it for the first time.)

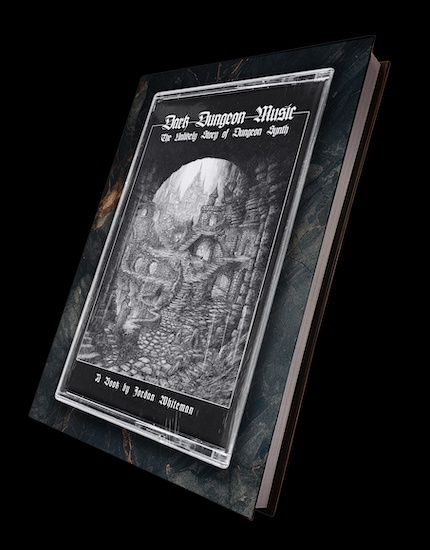

Released in December 2024 by Cult Never Dies, the book The Unlikely Story of Dungeon Synth became a good extension of the publishing house’s black-metal-oriented catalogue. It’s not something you would expect probably, but this subgenre, as a development of majestic synth-driven soundscapes accompanying a lot of black metal albums, has its history, its ethos, and influence too.

This well-written and well-illustrated book brightened up this January, so I decided to take a look behind the curtain and discover more of Dungeon Synth and its origin with the book’s author, Jordan Whiteman.

Hi Jordan! How are you? What’s going on in your lair?

Hey, thanks for having me here. I am seated by a window and there is roughly ten inches of snow on the ground. It is a good day.

Your book Dark Dungeon Music: The Unlikely Story of Dungeon Synth was released in December. How have things gone so far? Can you judge by the pre-order period how much the book is in demand?

I had very low expectations – some kind of psychological survival mechanism – so I am surprised by any interest in it at all. I’m only loosely aware of the quantified demand for it, but from what others tell me, it sounds like it is enjoying some respectable momentum.

I’m sure that Cult Never Dies ensures wide coverage of this release, but how did you get the deal with them? Did you try to find another publisher before?

Yeah, they’ve been great. I wouldn’t have been able to pull this off without them. In short, I just sent some early material to Dayal and we started discussing it and what it might look like. We kept in touch over the ensuing few months while I continued finishing drafts of different chapters. At some point, he sent over a contract, I signed it, and now we have a book. I didn’t really look for another publisher, but I spoke loosely with a U.S. publisher who had published a rather infamous black metal book. It never really left that stage of the conversation though.

You founded the label Ancient Meadow Records in 2017; dungeon synth and black metal bands were on your radar from the start. Did your work on the book serve as a continuation of your support of this underground’s segment?

In many ways, the book is a physical manifestation of my obsession with these genres of music. I’m hopeful that it is seen as a massive display of respect and reverence for dungeon synth.

Why did you decide to close the label in 2024?

There are myriad reasons, but chief among them was the constant workload keeping me from my daughter. I have a whole other life outside this music with a corporate job, a wife and kid, a mortgage, and all the other trappings of workaday life. Running the label while trying to finish this book and also manage all the rest was leading me to an early grave. I’m always impressed by people like Yosuke at NWN! who manage to do both for years on end. That said, AMR will never truly be “over”, “finished”, or “closed”. It will manifest in different ways in the years to come. I just need time away from it.

How did you come to understand that you were ready to take the first step and write down the entire genre’s story?

Honestly, it was the combination of my deep fascination with this genre and its history but also a healthy dose of spite for people hellbent on corrupting it through appropriation, misinterpretation, misrepresentation, parody, and other unfortunate circumstances of exposure to wider audiences.

As I understand, the book serves as an ultimate description and in-depth study of the genre. Do you feel now that everything was done right? Do you see that you could improve something in the text?

I don’t speak for everyone who has written a book, but I don’t think I could ever look at this book as though it were “finished”. Several times throughout the book, I lament that there are still many, many examples of this stuff from the 1990s that are lost to the time-eroding winds of history; “known unknowns”. I could have gone on trying to document all those old obscure projects for years.

There were also around three chapters that didn’t even make it into the drafts I sent for editing because I felt like I was just going to keep adding material and keep further delaying the book, which I had been working on for nearly four years by that point. Maybe someday that extra material will surface in an expanded and revised edition ten or fifteen years from now.

I definitely know there are places where I could improve things, and I know that more places where I could have improved things will only grow in number as time passes. I’ve had copies of the books on-hand for around a month now – I still sit and read through different parts of the book a couple of times a week. Not out of a sense of pride or conceit but out of some severe kind of self-loathing and compulsion to ruminate over my shortcomings again and again.

How comfortable was it for you to work on the book? Did you have any experience in musical journalism before, or was it just a natural extension of your work with the label’s promo stuff and so on?

It was taxing at times, mostly because I just kept trying to include more and more material in there. This genre is fascinating: the more you observe its origins and its glory days in the 1990s, the more you realize that there is a massive sea of this stuff out there that has yet to be discovered lurking just out of reach in the irretrievable past. I had to be more selective than I wanted to be in order to make printing the book a practical endeavor.

I’ve written for several publications in the past as a freelancer but this was my first foray into music journalism. I actually did my best to avoid mentioning my own label or artists explicitly associated with my label where it was possible, though of course it was something of an inevitability, as well. The publisher had to insist that a brief bio/informational snippet about AMR appear in the book under the premise of it being contextually necessary. I protested but eventually acquiesced to it [haha].

Did you reach all the bands you mentioned in the book individually? Were there any who refused to collaborate? Why?

Sadly, I did not. A lot of the artists/bands that I am concerned with from the 1990s haven’t actually been identified – so who they are remains a mystery. Further, some of those people from the 1990s are completely uninterested in acknowledging their music from their youth. I located one specific person from a duo project that has been a mystery to essentially everyone over the past 13-14 years, but as soon as they realized I wanted to discuss their music from the 1990s, they stopped responding. There were other cases where I wanted to have someone in the book or wanted to get them to scan old, rare tape inserts or fliers or something, or to complete an interview, and they just couldn’t find time (or motivation) to do it. I understood, though. Adult life is hard and time is scarce for most of us.

The book’s content is well-thought-out and you touch on crucial topics during your research such as dungeon synth’s origin, main inspirational themes, the equipment the artists use, and many more. How did you build the book’s structure? What were your main points?

Thank you for that. I wrote much of it out of sequence. The chapters I initially sent to the editors/publishers in my drafts were long, several of them in the 20,000+ words range. The editor was great about distilling and compartmentalizing the chapters into more digestible sections. In retrospect, some of the draft chapters were written in this kind of frenzied, panicked state – some kind of manic need to get the ideas out of my head and try to make them sensible.

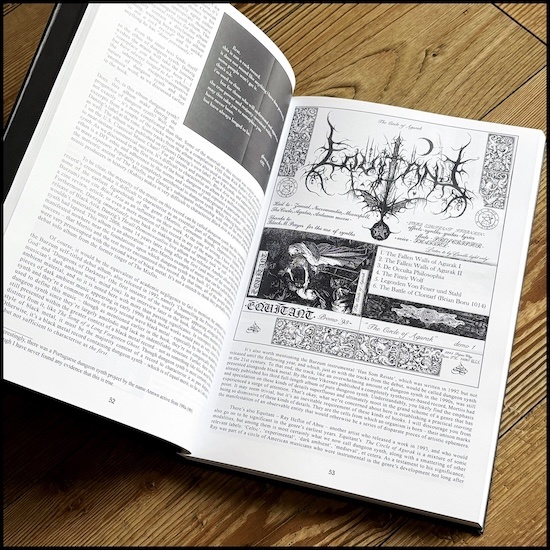

Overall, the book is a survey of the genre’s atomic origins, a primer for newcomers to get an accurate idea of what constitutes an example of dungeon synth, and a look at some cool artifacts from the genre’s history, some lesser-known artists and stories from the glory days, and other interesting exposés.

Sometimes it’s difficult to write about metal genres, because there are popular contradictions and disputes, like if a band belongs to one genre or another, or like if sludge relates to doom metal and so on. Did you meet such… let’s say… existential questions in your journey?

Oh yea, of course. Anyone who knows me knew to expect at least some exploration of those themes in this book. Though I did my best to avoid being overbearing on these topics, I did dedicate a short chapter to the modern appropriation of the genre and the false pretenses upon which its appropriation and distortion is made possible – primarily through a willful misuse of the concepts of “evolution” in art as a means of impugning the sanctity of the genre’s history and its true definition.

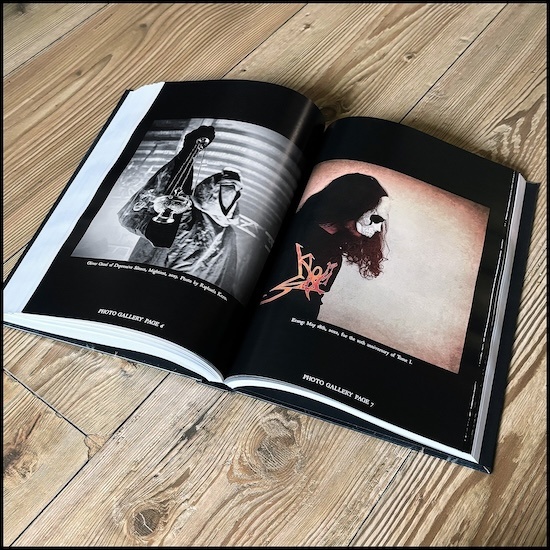

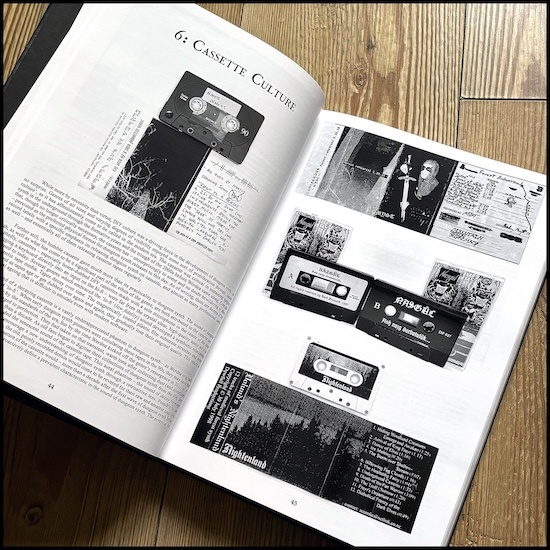

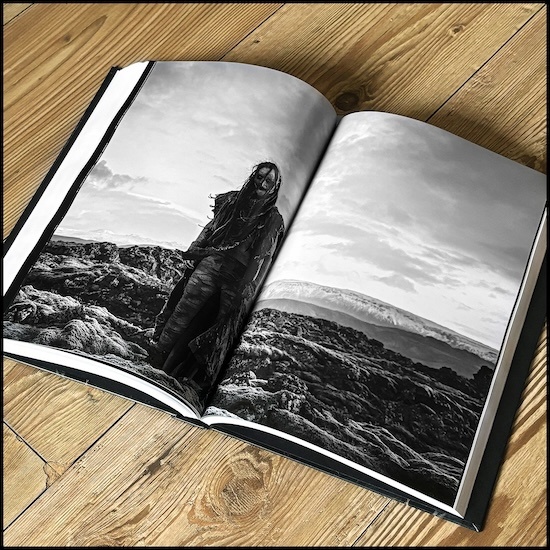

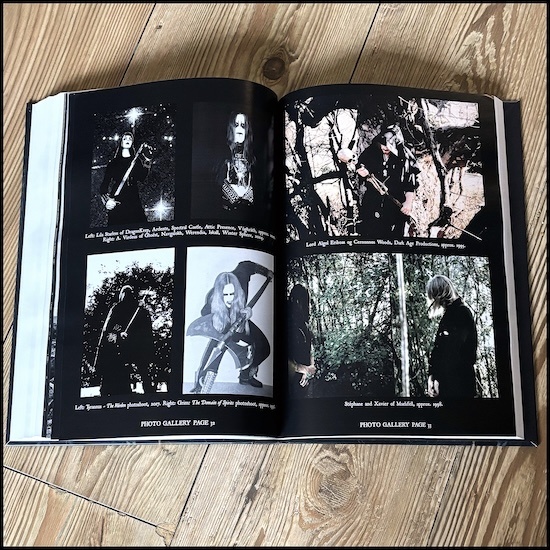

This book is richly illustrated, and that’s one of the Cult’s main points – to publish books that are attractive to readers, that are worth having in physical format. Was it hard to collect all those photos and illustrations?

You know, I am so grateful for Cult Never Dies and Dayal and the rest of his crew. He was outstandingly patient with me throughout the editorial process. I think there are something like 400 images in there that are not part of the center photo gallery and that’s after a 40% reduction (I’m making this number up) in the images used in my drafts versus what made it into the book. I spent years and years researching, gathering material, and developing the ideas in this book. I had thousands of images in my research folders, some of them extremely rare digital files that exist only in very low resolutions. I had to accept that they just could not be printed in any practical way. I’ve been thinking about setting up a sort of online archive of the research used for the book just to have a place to make sure those images get disseminated and archived in at least some meaningful way.

Okay, can you pick five core dungeon synth albums that you would recommend for those who would like to learn the genre’s basics?

Picking just five is a physical impossibility, so you get 10:

- Mortiis – Ånden som Gjorde Opprør

- Wongraven – Fjelltronen

- Black Wailing – Last Sunset

- Erevos – My Black Desires

- Arthame – Fiendish Symphonies

- Lamentation – Fullmoon Over Faerhaaven

- Depressive Silence – Mourning (a.k.a. ‘Demo ‘96’ or ‘Depressive Silence III’)

- Gothmog – Medieval Journeys

- Cernunnos Woods – Tears of the Weeping Willow

- Forgotten Pathways – Shrouded In Mystery

And can you name some artists or core albums which developed the genre and extended its borders a bit further?

These lists are non-comprehensive, obviously.

1990s Artists Who Cemented and Galvanized the Genre –

Mortiis, Valar, Mournlord, Summoning, Dark Art, Grim, Shadowcaster, Grabesmond, Balam, Norwegian Prison Guy, Nocturnal Funeral, Corvus Neblus, Wind/Varjosielu, Dark Funeral, Infamis, Golden Dawn/Aperion/Bannwald, Equitant, Toth-Ommog, Solanum, Pazuzu, Maelifell/Arden, Floral Of Forever/The Mystickal East/Noiratasya, Arcana Liturgia, Sagenhaft, Dragonwynd, Puritas Virginum, Mimir, Dark Forest, Lord Wolf, Druadan Forest, Empire of the Moon, Dolch, Lunar Womb, Secret Stairways, and on, and on, and on.

2000s Artists Who Cemented and Galvanized the Genre –

Elffor, Uruk-Hai, Vinterriket, Mittwinder, Myrrdin, Sirion, Skuty Lodem, Silence of Graveyard, Valscharuhn (this project belongs to the person who coined the phrase “dungeon synth”), Moloch, Gromoslaw, Mitternacht, and still more.

Modern Artists Who Embody the Core of the Genre –

There are literally thousands of projects active since the genre got a catchy name in 2011. It would be an exercise in futility to try and document all of those that earnestly serve to embody the spirit of the genre. To that end, look for anything from the modern era that shares the most visual, contextual, and sonic overlap with the champion examples from the 1990s and 2000s.

How do you see the genre’s development through the music of the bands you mentioned above? You know, for an ordinary listener or metal-head, dungeon synth is all the same most of the time.

Those bands and artists really chiseled out what constitutes the genre proper. They took the ethos and aesthetics of black metal over to electronic music and put the two together. They were the first to reach a juxtaposition between the two and produce something tangible out of it. Though there are some disparities between them, they are minor and not significant enough to make any of them questionably a part of the primordial dungeon synth aggregate. They have far more in common in all the right ways than they don’t.

I have this surprisingly unpopular perspective on music: music within genres is supposed to look and sound the same way. That’s the utilitarian function of a genre. They’re static containers that capture moments in an artist’s journey. “Development” and “growth” are concepts incompatible with genre, so one has to eschew their significance in order to appreciate and understand a genre of music as a body of work capturing very similar things over an indeterminate period of time. “Evolution”, “development”, and “growth” are things that happen to musicians, artists, bands, and so on. Those things don’t happen to whole genres because they’re antithetical to the most basic purpose of genres. It’s perfectly okay that artists want to pursue their idea of what those things look like, but they don’t get to take the genre with them once it has been defined at a meaningful scale.

You wrote separate chapters about the Devil and the Ethos in dungeon synth. Which role does ideology play in dungeon synth? It looks like a lot of bands don’t deal with things like this at all, as the music itself doesn’t demand it.

You’re right in that a lot of projects don’t explicitly bother with some ethical conundrum or ideology, and I preface the “ethos chapters” with a disclaimer that I personally don’t feel music or any mode of art ought to be expected to espouse some ethos, ideology, or other. To that end, however, dungeon synth coalesced in such a way that it’s evident there are some ethical tenets to the genre which merit exploration.

There are themes consistent throughout dungeon synth that suggest some underlying affinity for unspoiled nature, the human condition as despair and grappling with weighty philosophical issues like death and loneliness or (the absence of) objective purpose in life, an obsession with nostalgia and hauntology, anti-modernity, anti-Christianity, anti-religion on the whole, reverence of an irretrievable past, celebration of the D.I.Y. attitude in art, rejection of the spotlight, the brutality of humanity, and on and on.

Dungeon synth is irrevocably an “underground” genre. In its truest incarnations, it is utterly incongruous with the inclinations of the masses because the typical subjects it contends with, its sonic appeal, and its general aesthetics are outright shocking to a vast majority of the population. The sound of dungeon synth is highly specific, using modes typical of more morose, melancholic, or “dark” music, and it’s sonically minimal at times. That diminishes its appeal for a lot of people.

All this said, dungeon synth happily rejects popularity or mass appeal. It results in this sort of raw solitude for the artists. Dungeon synth makes no promises of fame or fortune, so the people making it enter into a subconscious agreement that they’re making something that will likely never reach a wide berth of listeners. In this way, dungeon synth presents the ultimate test to a musician: Make this music because you have to or else, because you will receive little external validation for your efforts. Making art simply because you have to get it out of you regardless of who hears it is the ultimate test of authenticity.

Do you have a plan for another book? Would you like to start another quest in another underground territory?

Indeed, I think I’ve got at least one more in me, but maybe even two. Writing this book only served to really illustrate just how much of the story is still waiting to be told. There are stories, artifacts, artists, and albums from the glory days of this music that deserve to be put into the historical account. Whatever self-loathing is compelling me to do that remains a mystery.

I’ve been discussing an idea with my friend Virdeus of Ghoëst. We’ve got archives of lots of these old articles, interviews, reviews, and exposés on this genre of music from the 1990s when it was still well within the nucleus of black metal. Hundreds of them, in fact. We put together a concept for a sort of rogue/guerilla compendium of all of that material solely to preserve and archive it for future generations as that material will only continue to fade into oblivion as more time passes.

By the way, did you ever play in a band yourself? I bet that after a work like this, you’re able to create a perfect dungeon synth project.

Oh yea, I’ve played in bands since I was a pre-teen. Music has always been a big part of my life and my own musical journey has been a lengthy process of evolution and changes, but I think a willingness to traverse genres and learn about new things is an essential ingredient in a healthy music diet. There are hundreds, thousands perhaps, of genres out there. I love that I found dungeon synth and I think I’ve done my due diligence to really learn it in a meaningful way; I hope I have, at least.

Not all genres are so interesting. Many of them are really just taxonomic containers, but some are bottomless rabbit holes and goldmines of discovery and intrigue. Naturally, in my journey with dungeon synth, I have dabbled at making some of it, but honestly what I have made wasn’t even really close. I was still learning about dungeon synth, still exploring the roots of the genre and trying to eke out what it had to teach me. None of it was very good because I’m too impatient with melodies and arrangement. My ADHD is too bothersome to really churn out something meaningful.

I’m bewildered at how some of the modern artists can seemingly make it in their sleep. I envy that. Mostly, I’ve been a drummer throughout my life because that role required the least amount of songwriting. If the world shows me any mercy, the music I have made in dungeon synth will not ever see any significant scrutiny. I would hate to subject fans to that [haha].

Thanks for the interview, Jordan, I hope that The Unlikely Story of Dungeon Synth will find its audience in all parts of the world, and we’ll have a chance to discuss another book of yours someday. Did we skip something important?

Thanks so much for listening to me ramble. I sincerely appreciate it. Thanks to you and No Clean Singing for providing this outlet for underground music, and doubly-so for providing this outlet for music that champions the uncomfortable, uneasy, and ugly parts of the human condition. It is a deeply necessary component of art. I’d like to thank my publisher Cult Never Dies for their trust in me, and I’d also like to thank all of my friends and collaborators in dungeon synth for just being there on this journey. I also want to extend my gratitude to everyone who ever supported AMR over the years or just had a discussion with me about this music.